In the global effort to address rising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, numerous nations, organizations, and entities have implemented carbon crediting mechanisms. Carbon crediting mechanisms comprise a system in which carbon credits, each representing the mitigation of 1 metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (1 tCO2e), are acquired through voluntary emissions reduction and avoidance initiatives. These initiatives encompass a range of activities, including carbon sequestration, afforestation, methane capture, and renewable energy activities. Carbon credits are issued (verified or certified) by any of the following1:

- International crediting mechanisms, which are established under international treaties, such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol;

- Independent crediting mechanisms, which are established by nongovernmental entities; and

- Domestic crediting mechanisms, which are established by regional, national, or subnational governments.

Examples for each implemented crediting mechanism type are summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Examples of Carbon Crediting Mechanisms1

| Carbon Crediting Mechanism Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| International | Clean Development Mechanism |

| Independent | Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve, Verified Carbon Standard, American Carbon Registry, Plan Vivo, |

| Domestic | Thailand Voluntary Emission Reduction Program, California Compliance Offset Program, Australia Emissions Reduction Fund, British Columbia Offset Program, Alberta Emission Offset Program, J-Credit Scheme, Canada Federal GHG Offset System |

Carbon crediting mechanisms generate a supply of carbon credits, with their value dependent on demand originating from various sources, such as1:

- International demand: Countries seek carbon credits to fulfill their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets under the Paris Agreement and other commitments to reduce emissions.

- Airline demand: Airlines use carbon credits to fulfill their obligations under the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA).

- Domestic demand: Some companies are required to comply with domestic laws, such as carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes (ETS), leading to a demand for carbon credits.

- Voluntary demand: Private organizations and corporations often seek carbon credits voluntarily to achieve their emissions reduction goals and sustainability targets.

Carbon credits issued are purchased by buyers for the purpose of offsetting carbon emissions or complying with emissions reduction regulations. In relation to the carbon credit demands, two distinct markets have emerged—the mandatory or compliance carbon market and the voluntary carbon market (VCM). The compliance market is established in response to compulsory national, regional, or international carbon reduction legislation, such as carbon taxes and ETS. On the other hand, the VCM serves as a platform for individuals and companies to engage in voluntary buying and selling carbon transactions. Compliance carbon credits tend to be more expensive than voluntary carbon credits due to their association with regulatory requirements. Also, it is important to note that voluntary credits cannot be used to fulfill regulatory requirements, unless explicitly stated otherwise. On the contrary, voluntary organizations have the option to acquire compliance credits for their needs2.

The World Bank observes an emerging trend as multiple countries establish their domestic carbon crediting mechanisms, often integrating them with emissions trading systems or carbon taxes. Examples of this include Indonesia and Vietnam, both of which instituted their own domestic crediting mechanisms in 2022. Additionally, India enacted legislation to establish its domestic crediting mechanism, paving the way for a potential integration with an ETS1.

The Present State of Carbon Crediting System Development in the Philippines

Plans for Establishing a Carbon Crediting System in the Philippines

In the Philippine context of carbon crediting systems in 2022, Secretary Maria Antonia Yulo-Loyzaga of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) advocated for the initiation of legislation aimed at formalizing the Philippines’ carbon crediting system in alignment with the nation’s climate transition objectives3. This concept was originally proposed by DMCI Mining Corporation, a subsidiary of DMCI Holdings Incorporated led by the Consunji group, and both the DENR Secretary and President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. have expressed their agreement with the proposal. The implementation of the system is estimated to be fully realized within approximately six years4.

In February 2023, the DENR is collaborating with Marubeni Corporation, DMCI Holdings unit Dacon Corporation (also known as Sirawai Plywood and Lumber Corporation (SPLC)), and the University of the Philippines – Los Baños College of Forestry and Natural Resources (UPLB-CFNR) to spearhead the development of a carbon credit program focused on reforestation5. The Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) was signed last May 15, 2023. Subsequently, a feasibility study for the project is scheduled to be conducted in Candoni, Negros Occidental, and other adjacent areas6. The primary objectives of this project are to restore biodiversity, generate employment opportunities for locals, and establish a carbon credit program by enhancing carbon absorption and sequestration through forest initiatives7. The project additionally seeks to foster partnerships among academia, industry, and government entities to contribute to the reforestation and sustainability efforts across the country6.

Promotion for the Philippines to Enter the Sovereign Carbon Credit Market

House Ways and Means Committee Chair Joey Salceda actively promotes the Philippines’ integration into the sovereign carbon credit market. In November 2023, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was signed between the Climate Change Commission and Maharlika Carbon Technologies Liability Limited Corporation, marking the Philippines’ involvement in the trading of Certified Emissions Reductions (CER), commonly referred to as voluntary carbon credits, and Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) among nations, which includes sovereign carbon credits. Under the terms of the MOU, the company will support the Philippine government in creating a registry that will be linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), enabling the Philippines to sell sovereign carbon credits to the global market. Sovereign carbon credits are generated by governments within the UNFCCC framework with the goal of combating deforestation and preserving forest ecosystems at a national level1. According to Salceda, this initiative holds the potential to yield climate-related benefits worth 14 billion USD for the Philippines8.

Retaliation of Environmental Groups for DENR’s Carbon Crediting System Plan

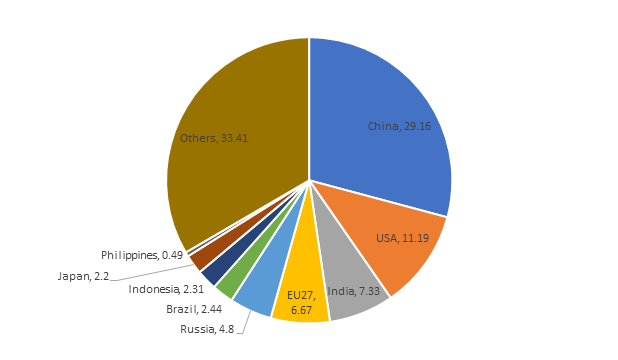

According to Chito Arceo, the National Education Coordinator of the Youth Advocates for Climate Action Philippines, the Philippines is unlikely to derive significant benefits from carbon credits due to its relatively low GHG emissions9 (only 0.49% of global emissions in 2022), unlike China (29.16%), United States (11.19%), India (7.33%), and 27 countries in EU (6.67%)10. Arceo suggests that the government should prioritize enhancing climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, given the country’s susceptibility to natural disasters. Criticism has been directed at the government for lacking long-term plans in disaster risk reduction and management, being primarily reactive to extreme weather events9. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), extreme natural disasters costed the country 497.457 billion PHP in damages, which is roughly 8.95 billion USD, between 2012 and 202211.

Figure. Percentage of Global GHG Emissions Share in 2022. It can be seen that China, the USA, India, and the EU27 are leading in GHG emissions globally10. EU27 consists of 27 countries which are Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, and Sweden as of February 1, 202012.

Carbon Credits, ETS, and Carbon Taxes: Potential for Revenue

The generation of carbon credits serves not only to accomplish GHG emissions targets but also offers revenue opportunities for companies and organizations. At the governmental level, the establishment and implementation of ETS and carbon taxes were noted by the World Bank to yield substantial revenues in 2022, witnessing a 10% improvement from the previous year. Revenues reached an estimated 95 billion USD globally, with EU ETS generating the most revenue (42 billion USD). The revenues from ETSs and carbon taxes are primarily allocated for governments’ green spending. It is also observed by World Bank that while emerging countries are beginning to participate in carbon markets, high-income economies continue to dominate this space1.

Introducing an ETS or carbon taxes in the Philippines has the potential to secure additional funding for climate transition projects. As highlighted in earlier sections, an increasing number of countries are establishing domestic crediting mechanisms alongside an ETS. For the Philippines, the logical step, in conjunction with the development of the carbon crediting mechanism, is to explore the adoption of an ETS or carbon tax, which unlocks the potential of the compliance carbon market within the country. This move not only offers increased revenue opportunities, but also serves as an incentive for both private and public entities to actively participate in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and reforestation. Disaster risk mitigation and adaptation should also be prioritized to reduce additional damages and the loss of lives resulting from natural disasters.

References

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023. https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2023/World%20Bank%20State%20and%20Trends%20of%20Carbon%20Pricing%202023.pdf (2023) doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-2006-9. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) & Greenhouse Gas Management Institute (GHGMI). Mandatory & Voluntary Offset Markets. Carbon Offset Guide https://www.offsetguide.org/understanding-carbon-offsets/carbon-offset-programs/mandatory-voluntary-offset-markets/.

- Rivera, D. Law for carbon credit systems in Philippines pushed. PhilStar Global https://www.philstar.com/business/2022/12/12/2230138/law-carbon-credit-systems-philippines-pushed (2022).

- Lagare, J. B. Carbon credit trading may soon be a thing in PH, says DMCI unit. The Inquirer https://business.inquirer.net/374969/carbon-credit-trading-may-soon-be-a-thing-in-ph-says-dmci-unit (2022).

- Talavera, S. J. DENR partners with private sector, academe for reforestation carbon credit program. BusinessWorld https://www.bworldonline.com/the-nation/2023/02/12/504378/denr-partners-with-private-sector-academe-for-reforestation-carbon-credit-program/ (2023).

- Oleta, A. V. G. & Dalangin, K. R. F. CFNR to develop joint carbon credit program with Marubeni PH and SPLC. University of the Philippines – Los Baños https://uplb.edu.ph/all-news/cfnr-to-develop-joint-carbon-credit-program-with-marubeni-ph-and-splc/#:~:text=The%20UPLB%20Foundation%2C%20Inc.,%2C%20and%20revegetation%20(ARR). (2023).

- net. Marubeni to help develop PH reforestation carbon credit program. The Inquirer https://business.inquirer.net/385981/marubeni-to-help-develop-ph-reforestation-carbon-credit-program (2023).

- Cervantes, F. M. Solon pushes for PH entry into sovereign carbon credit market. Philippine News Agency https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1214300 (2023).

- Formoso, M. Environmental Groups Blast DENR Plan for Carbon Credit Systems. Philippine Collegian https://phkule.org/article/800/environmental-groups-blast-denr-plan-for-carbon-credit-systems (2023).

- Crippa, M. et al. GHG emissions of all world countries. https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/report_2023 (2023) doi:10.2760/953322, JRC134504.

- Ordinario, C. U. Disasters cost PHL P500.7B in past decade–PSA report. BusinessMirror https://businessmirror.com.ph/2023/06/29/disasters-cost-phl-p500-7b-in-past-decade-psa-report/#:~:text=Based%20on%20the%20Compendium%20of,events%20and%20disasters%2C%20while%20P3. (2023).

- European Commission. EU-27. European Commission https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/glossary/eu-27#:~:text=Abbreviation%20of%20European%20Union%20(EU,Slovakia%2C%20Finland%2C%20Sweden)%2C (2020).

The Philippines’ Legislative Initiatives on Carbon Crediting Systems

The Philippines’ Legislative Initiatives on Carbon Crediting Systems