Importance of Nuclear Energy in a Nutshell

Nuclear energy, a cornerstone of modern power generation, has been a subject of both fascination and controversy since its inception. Leveraging the immense energy obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear power plants have become vital contributors to the global energy landscape. One of the primary uses of nuclear energy globally is electricity generation. Nuclear power plants harness the heat produced by nuclear fission to generate steam, which in turn drives turbines to produce electricity1. This form of energy generation is renowned for its reliability and ability to provide consistent baseload power2, making it a crucial component of many countries’ energy portfolios.

Amid growing concerns about climate change and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, nuclear energy emerges as a significant player. Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear power plants produce electricity without emitting greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide3, making them a valuable tool in mitigating climate change and transitioning towards cleaner energy systems. Nuclear energy enhances energy security by diversifying energy sources and reducing dependency on fossil fuels, which are subject to geopolitical uncertainties and price fluctuations. Countries with significant nuclear power capacity often enjoy greater energy independence and resilience against disruptions in the global energy market3,4.

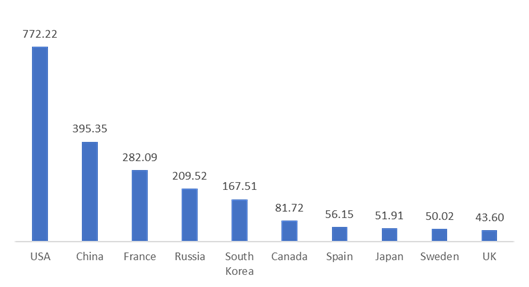

The top nuclear energy producers in 2022 are the United States of America, China, France, Russia, the Republic of Korea, Canada, Spain, Japan, Sweden and the United Kingdom5 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nuclear energy production in TWh of the top countries in 2022. Data from International Atomic Energy Agency – Power Reactor Information System5

Overview of ASEAN’s Nuclear Energy Progress

The ASEAN has demonstrated varying degrees of progress in the development and utilization of nuclear energy among its member states. While some countries in the region have actively pursued nuclear energy programs, others have shown reluctance or limited interest due to concerns related to safety, security, environmental impacts, and economic viability.

Here is summarizes the highlights of ASEAN’s and the member states’ current stance and progress on nuclear energy.

Cambodia

In 2016, the National Council for Sustainable Development of Cambodia signed two memoranda with Rosatom, a nuclear energy company. One memorandum pertained to the establishment of a nuclear energy information center in the country, while the other aimed to create a joint working group to promote the peaceful usage of atomic energy6,7.

In the same year, the Ministry of Industry, Mines, and Energy engaged in talks with the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) regarding the construction of a nuclear power plant. They also discussed establishing the necessary regulatory and legal frameworks for this endeavor, collaborating with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)7.

Indonesia

In February 2014, the National Energy Policy (NEP) of Indonesia strongly pushes for the growth and use of new renewable energy (NRE), which includes nuclear, and a target of 4000 MW was set for installed nuclear capacity8.

Since 1989, various feasibility studies on potential sites for small and large-scale nuclear power plants were done in the country. In December 2022, Indonesia set its sights on constructing a nuclear power plant by 2039. Indonesia’s Nuclear Energy Regulatory Agency, known as Badan Pengawas Tenaga Nuklir (BAPETEN), is actively seeking investors to support the financing of the plant’s construction8.

Laos

In September 2015, Rosatom was considering the construction of two 1000 MWe nuclear power reactors in Laos under a build-operate-transfer arrangement, with plans for power exports to Singapore. By April 2016, Rosatom had entered into an agreement with the Ministry of Energy and Mines to collaborate on the design, construction, and operation of nuclear power plants and research reactors. In September 2017, Rosatom and Laos signed, a roadmap outlining cooperation in the peaceful uses of atomic energy. Subsequently, in July 2019, two additional agreements were signed between Rosatom and the Ministry of Energy and Mines, focusing on education, personnel training, and shaping public opinion regarding the use of nuclear energy7.

Malaysia

The Malaysian Nuclear Agency (MNA), which was previously known as Malaysian Institute for Nuclear Technology Research (MINT), was established in 1972, focusing on research and operation of the TRIGA Puspati research reactor7,9.

In January 2011, the Malaysia Nuclear Power Corporation (MNPC) was established as part of the new Economic Transformation Program (ETP) with the goal of leading the eventual introduction of nuclear power plants within a 12-year timeframe. Although in 2018, the new government announced its decision to halt the development of nuclear power within the country and to cease MNPC’s operations7 due to the environmental issues and public opinion surrounding nuclear energy generation10.

Myanmar

In June 2015, similar to Cambodia, Rosatom and Myanmar’s Minister of Science and Technology signed memoranda aimed at establishing a nuclear energy information center and advancing the peaceful use of atomic energy within the country7.

In February 2023, Myanmar entered into an intergovernmental agreement with Russia, outlining the plans for the two nations to jointly construct an RITM-200 55 MWe SMR (small modular reactor). Furthermore, Myanmar is currently in the process of formulating domestic laws concerning nuclear energy7.

Philippines

Due to the 1973 oil crisis, the Philippines initiated the construction of a nuclear power plant. The 621 MWe Westinghouse unit located in Bataan was finalized in 1984 but never put into operation as a result of financial constraints and safety concerns related to earthquakes. Following the Chernobyl accident in April 1986, the plant was decommissioned11.

In the 2008 National Energy Plan, it was projected that 600 MWe of nuclear power would be operational by 2025, with additional increments of 600 MWe in 2027, 2030, and 2034, totaling 2400 MWe. Moreover, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) suggested in the same year that Bataan could be refurbished and operated economically for 30 years. In December 2008, the National Power Corporation (Napocor) enlisted the Korea Electric Power Corp to conduct an 18-month feasibility study on reactivating Bataan. By May 2013, Napocor was urging the government to refurbish and commission the plant to address power shortages and steep increases in electricity prices11.

Currently, the potential refurbishment of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant remains under consideration, with the Department of Energy (DOE) also exploring the possibility of constructing a new nuclear plant utilizing SMR technology and conducting feasibility studies11.

In January 2023, preparations were announced for establishing a legal framework facilitating the transfer of U.S.-origin special nuclear material and the export of nuclear fuel, reactors, and equipment for social use between the U.S. and the Philippines11.

In February 2024, the DOE established the Nuclear Energy Program Coordinating Committee to oversee the implementation of the country’s nuclear energy program and is responsible for drafting recommendations to accommodate new nuclear capacity on the country’s electric grid, developing national legislation for nuclear energy, defining requirements for potential nuclear power plant locations, and ensuring environmental protection11.

Singapore

In 2012, the Singapore Nuclear Research and Safety Initiative (SNRSI) was founded at the National University of Singapore (NUS) to centralize expertise in the field of nuclear energy. The government is currently monitoring global trends in nuclear energy7.

Thailand

From 2008 to 2011, the Energy Minister of Thailand allocated $53 million for preparatory work and feasibility studies on the construction of a nuclear power plant unit, scheduled to begin in 2014. While five potential sites were identified, resistance from local communities led to the elimination of three sites in 2010. Assessing potential sites proved challenging due to local opposition, influenced by past experiences with industrial developments and the country’s political climate. Recognizing the importance of public information and community consultation, these areas were identified as top priorities. However, construction plans were halted following the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear plant accident in Japan7.

In Thailand’s 2015 Power Development Plan, the Ministry of Energy outlined the addition of 2000 MWe of nuclear power by 2036. Thailand has operated a research reactor since 19777.

Vietnam

Since the early 1980s, Vietnam has been conducting preliminary studies on nuclear energy. In February 2006, Vietnam announced plans to construct a 2000 MWe nuclear power plant by 2020, as part of a nuclear power development plan approved by the government in August 2007. Subsequently, the target capacity was increased to 8000 MWe by 2025. Vietnam’s Atomic Energy Law, passed in June 2008 and effective from early 2009, established a national nuclear safety commission responsible to the Prime Minister for safety and licensing, which was formed in July 201012.

Initially, Russia had agreed to finance and build 2400 MWe of nuclear capacity starting from 2020, while Japan had agreed to a similar arrangement for an additional 2200 MWe. However, in November 2016, the National Assembly passed a resolution postponing indefinitely the construction plans for the two nuclear power stations. These would be replaced with 6 GWe of LNG and coal by 203012.

In March 2022, the Ministry of Industry and Trade released a draft development plan for the integration of SMRs into the country’s energy mix after 203012.

Risks of Nuclear Energy

Despite its numerous benefits, the utilization of nuclear energy also raises concerns, with the most prominent being safety, particularly in the aftermath of catastrophic events such as the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. These incidents underscore the potential for catastrophic accidents, highlighting the risks associated with the operation of nuclear power plants, including reactor meltdowns, radioactive releases, and their detrimental effects on human health and the environment. Although, these are only the major accidents that occurred in 36 countries that have nuclear power operations. Thus, showing that the risk of accidents is declining4.

Even though nuclear energy is considered as low-carbon, nuclear energy is not without environmental consequences. The mining and processing of uranium contribute to environmental degradation. Additionally, concerns persist regarding the long-term environmental effects of radioactive contamination and nuclear waste disposal and transport. Radioactive waste remains hazardous for thousands of years, necessitating secure storage facilities that must withstand geological and human-induced threats. The lack of permanent disposal solutions and public opposition to nuclear waste repositories exacerbate this issue, raising questions about the long-term sustainability of nuclear energy13.

The high initial costs of nuclear power plant construction, coupled with lengthy project timelines and regulatory uncertainties, render nuclear energy economically challenging compared to alternative energy sources such as solar and wind power. Cost overruns and delays in nuclear projects further undermine the economic viability of nuclear power, leading to questions about its role in a rapidly evolving energy landscape13.

Conclusion

Overall, while nuclear energy holds potential as a low-carbon energy option for ASEAN countries seeking to diversify their energy portfolios, progress with nuclear energy production has been slow and varied across the region due to concerns over safety and financing. Some countries are shifting priorities towards other renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind. The future of nuclear energy in ASEAN will likely depend on factors such as technological advancements, regulatory frameworks, public acceptance, and the evolving dynamics of the global energy situation.

References

- S. Energy Information Administration. Nuclear explained: Nuclear power plants. U.S. Energy Information Administration https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/nuclear/nuclear-power-plants.php#:~:text=Nuclear%20power%20comes%20from%20nuclear,magnetic%20generators%20to%20produce%20electricity (2023).

- International Energy Forum. Nuclear Power: Low-Carbon, Reliable – and Innovative. International Energy Forum https://www.ief.org/news/nuclear-power-low-carbon-reliable-and-innovative (2022).

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Energy and Sustainable Development. World Nuclear Association https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/energy-and-the-environment/nuclear-energy-and-sustainable-development.aspx (2022).

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power and Energy Security. World Nuclear Association https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/economic-aspects/nuclear-power-and-energy-security.aspx (2022).

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Nuclear Share of Electricity Generation in 2022. Power Reactor Information System https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/WorldStatistics/NuclearShareofElectricityGeneration.aspx (2024).

- History of Cooperation. Rosatom https://www.rosatom-asia.com/rosatom-in-country/history-of-cooperation/.

- World Nuclear Association. Emerging Nuclear Energy Countries. World Nuclear Association https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/others/emerging-nuclear-energy-countries.aspx (2023).

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power in Indonesia. World Nuclear Association https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/indonesia.aspx (2022).

- Malaysian Nuclear Agency. TRIGA Puspati Reactor. Malaysian Nuclear Agency https://www.nuclearmalaysia.gov.my/eng/kemudahan-rnd.php?id=1

- The Star. Malaysia keeps ‘no nuclear policy’ stance on power generation, says Nik Nazmi. The Star https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2023/07/20/malaysia-keeps-039no-nuclear-policy039-stance-on-power-generation-says-nik-nazmi (2023).

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power in the Philippines. World Nuclear Association https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-o-s/philippines.aspx (2024).

- World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power in Vietnam. World Nuclear Association https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-t-z/vietnam.aspx (2022).

- Natural Resources Defense Council. Nuclear Power 101. Natural Resources Defense Council https://www.nrdc.org/stories/nuclear-power-101#problem (2020)

The Status and Progress of Nuclear Energy in the ASEAN Region

The Status and Progress of Nuclear Energy in the ASEAN Region